Submitted - APRIL 04, 2022 | Accepted - OCTOBER 4, 2022 | ePublished - December 31, 2023

https://doi.org/10.52733/KCJ21n3-r3

ABSTRACT

Achieving patient-centered care requires helping patients understand their illness, eliciting patient values, and developing a collaborative care plan with input from patient and physician. Combining existing models in communication skills and shared decision making provides a road map for accomplishing these tasks in delivering patient-centered care. In this article, we highlight the importance of patient understanding of their prognosis as a key step in delivering patient-centered care. We then review literature suggesting that both patient and patient’s physicians’ emotions play an inhibitory role in accurate formulation and communication of prognosis by physicians and accurate incorporation of this information by patients. We postulate that the finding of benefit of early integration of palliative care (PC) in improving patient-centered outcomes may be addressing these inhibitory factors. Key skills of empathic communication by a PC team that is focused on addressing patient emotions may facilitate better understanding of prognosis and thus improved patient-centered decision leading to improved patient centered outcomes. Finally, we propose advances treatment of renal cell carcinoma makes it an ideal disease that can inform this hypothesis of how integration of PC works. Specifically, we propose that the curability potential in metastatic RCC, amplifies challenges associated with patient prognostic understanding and decision making. Studying which discipline – primary oncology team or palliative care team – can help patients achieve more accurate prognostic understanding leading to more patient centered choices and improved patient-centered care.

KEYWORDS

Palliative Care, Renal Cell Carcinoma, Kidney Cancer

INTRODUCTION

“The secret of the care of the patient is caring for the patient.”

- Francis Peabody, 1921

Early integration of palliative care (PC) has been advocated

in routine oncological care in the past decade based

on studies showing improvement in patient symptoms,

quality of life and survival 1-7 . Despite these recommendations,

retrospective review of inpatient and outpatient data

shows that most patients do not receive palliative care services

as recommended by the guidelines, including patients

with kidney cancer 8-10. At the same time, the mechanism by

which improvement in patient centered outcomes including

survival are achieved by integration is not clear.

In the United States, an estimated 79,000 new cases and about 14,000 deaths due to kidney and renal pelvis cancer are projected to occur in 2022 alone11. Over 90% of kidney cancer cases are due to renal cell carcinoma (RCC). About 30% of patients initially present with metastatic RCC and another third of patients will have cancer recurrence with distant metastases after extirpative surgery12,13. With recent advances in immunotherapy, the landscape for treatment and outcome of RCC has changed ushering in multitude of challenges and opportunities14. Here, we focus on one of these challenges, providing accurate prognostic understanding, and the representative opportunity it represents to study the mechanism of palliative care interventions. Advances in treatment has led to additional prognostic uncertainty of “can I be cured?” to the existing prognostic uncertainty of “how long do I have, doctor?” By integrating palliative care into routine RCC care, we propose to study which discipline in the multidisciplinary team can help patients achieve more accurate prognostic understanding, leading to improved decision making and, patient outcomes.

Importance of accurate prognostic understanding

Studies of early palliative care integration demonstrated survival benefits in patients receiving early integration of palliative care5, 15. In one study, at the time of the early integration of PC in metastatic lung cancer, disease was deemed incurable, and yet at baseline, 32% of patients expected that their metastatic disease was curable, and 69% reported that elimination of all cancer was a reasonable goal of treatment. With integration of monthly palliative care visits, a greater percentage of patients in the early palliative care arm were noted to have cultivated an accurate understanding of prognosis (82.5% vs. 59.6%). Furthermore, the authors found that patients having an accurate understanding of disease prognosis and undergoing palliative care treatment were least likely to opt for aggressive and standard of care intravenous chemotherapy treatment within 60 days of death15. The study reported survival benefits in patients with early palliative are arm. It also showed that those with more accurate improved prognostic understanding chose less chemotherapy5,15. Thus, improved, and accurate illness and prognostic understanding and decisions based on accurate prognostic understanding likely play a role in patient outcomes which aligns with our goals of patient-centered care and shared decision making (SDM).

FIGURE 2. Model of palliative interventions in curative and palliative setting for kidney cancer

Model for Conveying Accurate Prognostic Understanding – Communication Skills and Shared Decision Making

We can view the importance of accurate prognostic understanding in a larger context of patient-centered care. Institute of Medicine defined patient-centered care as “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions”16. Thus, physicians must accomplish at least two major tasks to provide patient-centered care, 1) to elicit and understand the patient’s preferences, needs, and values and 2) to develop a collaborative plan with the patient that respects and honors their preferences, needs, and values.

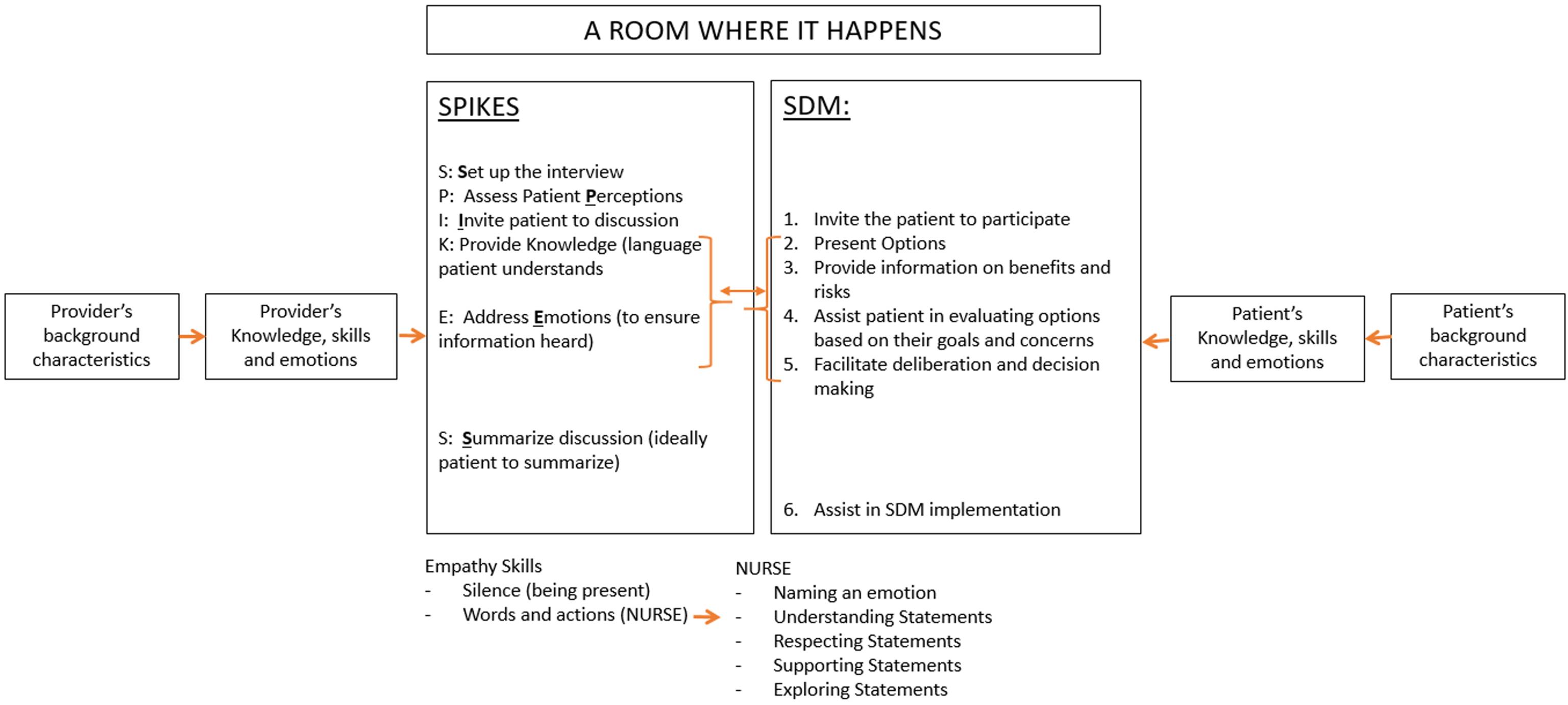

There are two separate models that accomplish these

two goals. A communication skills (CS) model, SPIKES, that

provides a roadmap for building rapport, eliciting patient

preferences, needs and values by using skills such as active

listening, reflection, and empathic communication17. A

shared decision making model allows for the development

and implementation of a collaborative plan with input

and collaboration from patients and physicians18. SDM

ensures that among the various treatment choices, patient

preferences and values are guiding the decision. Together,

communication skills and shared decision making provide

specific tasks for physicians and patients to complete to

achieve optimal patient-centered care.

These two tasks can be modeled in a combined CS and

SDM models into one as shown in Figure 1. In this combined

model, when a patient and a physician come together to

make a decision, the SDM model acknowledges that they

both bring their own worldview to the discussion. These

worl`dviews are shaped by individual background, lived

experiences, knowledge, and emotions18. These worldviews

shape the perceptions of the conversation between a patient

and a physician, and the decisions are made based on these

perceptions. These perceptions are what can be assessed by

physicians when listening to a patient’s story initially as they

build a rapport with the patient and family. The language

and vocabulary used by the patient can provide a window

into that patient’s perspectives that will help or impede

future decision making. In addition, the physician needs to

elicit patient preferences and values along with their hopes

and fears by listening and asking direct questions. Physician

uses principles of empathic communication throughout the

conversation and over the long term relationship including

use of open-ended and guided closed-ended questions17.

Once the physician has had a good understanding of the

disease and patient goals and preferences, they can invite the

patient to start the decision-making process for therapies.

The process includes reviewing options for therapies in a

stepwise and iterative manner. For each therapy choice,

risk and benefits are explained and understood and how

they impact patient preferences and goals are highlighted.

Given this can be emotionally challenging and cognitively

overwhelming conversation, the physician needs to conduct

the conversation with great empathy, including using the

non-verbal skills of silence and reflective listening and verbal

skills to ensure patients hear and understand what is said.

Examples of these verbal skills include: Naming an emotion

(N), Understanding statements (U), Respecting statements

(R), Supporting statements (S) and Exploring statements (E)

or commonly referred to as NURSE acronym19.

Although shown in Figure 1 as a series of steps, providing

information is likely to be an iterative process with multiple

pauses, iterations, and restart of the conversation to ensure

that the patient understands their disease, their treatment

goals, and their potential treatment options including risks

and benefits of each of these options. The physician uses

patient’s own words and language to increase the odds

that the patient hears and understands what is being said.

This iterative process allows the physician to guide the

discussion with the patient and families, while eliciting and

refining patient values and preferences. Finally, once all the

discussions have occurred and they can be a collaborative

agreement on best treatment option and specific next steps.

The physician can ask the patient to summarize the patient’s

understanding to ensure all have mutual understanding of

the discussion and the collaborative plan.

Patient and Physician Emotions Are Key

Intermediaries to prognostic understanding

As shown above, to achieve a patient-centered decision,

the physician first must understand the patient worldview

including their goals, values, and preferences, and then

provide information that is heard and understood by the

patient. The information can include prognostic information.

After obtaining a mutual understanding, the physician then

needs to help the patient make decisions that are aligned

with that patient’s goals. The key to this complex process is

the fundamental of CS, empathic communication as shown

in Figure 1.

Both patient and provider emotions play a key role in

what and how information is conveyed and what was heard

during the above conversation. If the conversation or patient

understanding is suboptimal, it may lead to patients making

choices incongruent to their values and preferences. The

challenge thus is both patient and physician emotions.

For example, two separate studies showed potential impact

of physician emotions on formulating and communicating

prognosis. In one study, a longer the physicians had known

the patient, more likely the physician would err in their

prognostication [20]. In a different study, what physicians

told the researchers about prognosis (formulated prognosis)

was and what they told patients (communicated prognosis)

differed by more than 20% and both were significantly

inaccurate (for example, communicated 90 days survival

estimate when actual was 26 days)20, 21. Thus, both conscious

and unconscious optimism, possibly from provider emotions,

plays a role in formulation and communication of inaccurate

prognosis21.

Similarly, patients’ emotions and world view may

impact what they hear and how they make decisions. Aim

of phase 1 studies is to assess for dose limiting toxicities

and optimal dose for future research and involve first in

human drug or combination of drugs. Review of informed

consents have shown that there is almost never a promise of

direct benefit to subjects, rarely mention cure, and usually

communicate seriousness and unpredictability of risk22.

Despite their consent, patients participating in these trials reported a different perception and that provides insights into how patients perceive and make decisions. In a large multi-centered study of one hundred-sixty-three patients participating in phase 1 studies showed that 75% of patients felt the pressure to participate because their cancer was growing and similar percentage of patients reported feeling somewhat or very anxious when they were not receiving some sort of anti-cancer therapies [23]. More interestingly, only 3% of participants reported they personally were very or somewhat unlikely to benefit from participating in the phase 1 study even though 60% of them estimated that others were unlikely to benefit23.

In a different study of patients being evaluated for phase 1

studies showed that those patients who enrolled in the phase

1 study reported higher likelihood of response to therapy

compared to patients that did not enroll or physicians who

had consulted with them24. Thus, patients perceive and

process information thru the lens of their emotions and

worldview which may lead to more inaccurate expectations

of benefit of therapy.

Thus, physician and patient emotions can prevent

accurate prognostication and communication of the prognosis

by the physician and can lead to patients making decisions

without accurately understanding of their prognosis and its

implications on their therapy options and likely outcomes.

Thus, a decision made with inaccurate information can lead

to flawed and ultimately poor decisions such as continuing

ineffective therapies or taking therapies that are unlikely to

benefit and may even be counterintuitive to their stated goals.

Integration of Palliative Care in RCC and Exploration of Mechanism of action of Palliative care

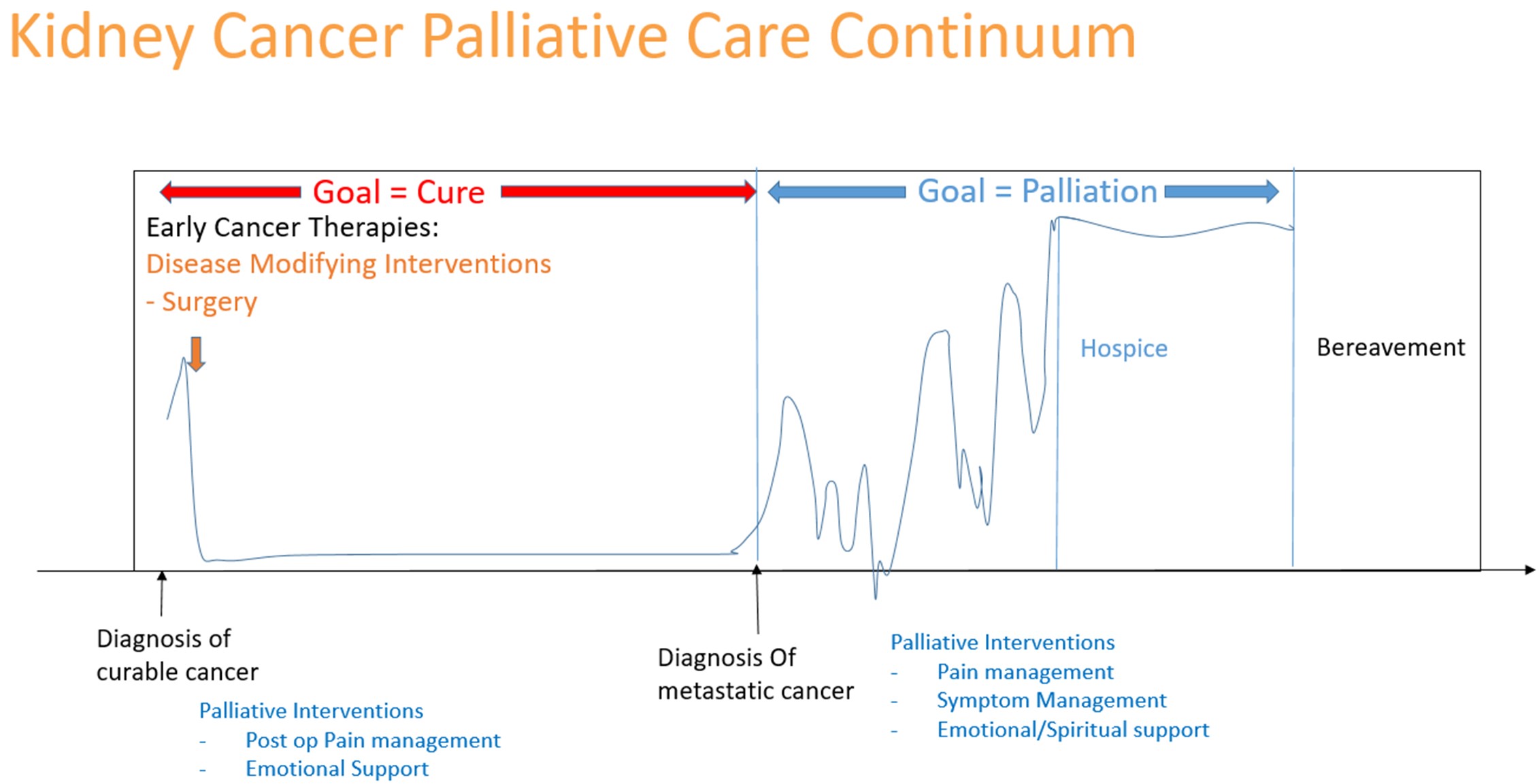

Palliative care is specialized medical care delivered by a multidisciplinary team of physicians, nurses, social workers, and other specialists addressing multiple domains of care.25, 26. Palliative care team focuses on symptom management as well as provides expert communications with patients and caregivers. The expert communication, as shown in the Figure 1, involves addressing emotions with empathy. When symptom management and expert communication are provided by the primary oncology team, it is called “primary palliative care” and when using a subspecialty team, it is called “subspecialty palliative care”27. Post-operative pain by the urologist; prevention and treatment of side effects of medical therapies by the medical oncologists; radiation to alleviate pain from bone metastasis by the radiation oncologists are all examples of delivery of primary palliative care delivered by the oncology team. In addition to these symptoms, one or more of the primary teams can discuss treatment goals and address patient emotional and spiritual needs. When needed, these primary teams can consult with subspecialists to help them manage patient’s symptoms or communications, it would be considered specialist palliative care. Using this definition, we can conclude that palliative interventions start concurrently with curative treatments, continue alongside palliative intent therapies, until a point where focus changes to providing comfort, eventually transitions to hospice (Figure 2).

All the challenges to SDM listed above with inaccurate

prognosis, communication, and patient perceptions have

been studied prior to advances in oncologic therapies such

as immunotherapy. Immunotherapy, and specifically

immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy, has changed the

landscape of management of RCC. Prior to the advances in

immunotherapy, the answer to the question “can I be cured”

when presenting with metastatic disease was “no” with

confidence ad now, it is much more nuanced. Recent phase

III studies with combination of immunotherapies show that

even with metastatic disease, up to 7-16% patients can have

long-term complete remission and may be even cured28-31.

This creates a further challenge and an opportunity in

communicating prognosis to achieve patient centered

decision using SDM.

This challenge of difficulty in communicating

‘curability’ highlighted in a study of patients with advanced

lung cancer and genitourinary (GU) malignancies receiving

immunotherapy32, 33. Approximately 20-95% of patients

had an inaccurate understanding of their curability and

had increased anxiety compared to those with an accurate

understanding of their cancer34.

Considering the challenge of prognostic uncertainty

caused by improved RCC outcomes and the observation that

palliative care integration has been shown to both improve

prognostic understanding and contribute to the making of

more patient-centered decisions, RCC is an ideal disease in

which to study how palliative care improves patient survival.

There is already pilot data of integration of palliative

care into routine RCC care in the immunotherapy era27. We

hypothesize that using the model for decision making above

and understanding how the above tasks are completed,

we may be able to understand the mechanism by which

integration of palliative care enhances patient outcomes. We

further hypothesize that the advances in RCC treatment in

the past decade with increased uncertainty makes it an ideal

disease to study and elucidate these mechanisms that can

then be utilized in other diseases.

Mechanisms include improved patient prognostic

understanding via improved management of patient emotions

and communication. As studies have showed that the longer

an oncologist knows a patient, accurate prognostication

becomes more difficult, and it becomes even harder to

communicate this prognosis accurately, an independent

palliative team may have less emotional burden to facilitate

an honest conversation20, 21. A separate team that is focused

solely on patient symptoms including emotional symptoms,

also allows patients increased opportunities to feel “cared

for,” as was highlighted by Dr. Peabody, without getting

chemotherapy and scans.

We hypothesize that potential mechanisms of the benefits

from palliative care may include:

• Improved illness communication, through improved physician understanding of patient worldview and management of patient emotions

• Improved prognostic understanding leading to improved shared decision making

Patients with RCC undergoing concurrent oncological

and palliative care can be assessed along with each team for

how information is conveyed and heard by the patient. While

both the primary oncology team providing palliative care

can be skilled, the context of the conversations with patients

who are focused on cancer and therapies may preclude

accurate exchange of information due to the emotional

reactions from both patients and the primary team.

Having a subspecialty palliative care team with expertise

in symptom management and communication skills may

allow patients and the PC team to have discussions in a

non-cancer treatment context, which may facilitate better

information incorporation and even improved decision

making.

By evaluating how information on diagnosis,

staging and treatment goals are discussed, how patient

understands them and how the discussion of prognosis is

conducted, and decision made to start, continue, change, or

stop cancer directed therapies will allow us to understand

the role primary oncology and palliative care team plays

in improving patient understanding and decision making.

An improved mechanistic understanding of how

palliative care team impacts patient outcomes may help

guide future implementation and research. Understanding

whether the primary team, due to its relationship with

the patient, is likely to be handicapped in an objective

discussion may facilitate better identification of when and

how to integrate palliative care. Understanding which

factors predict which patients view and relate to primary

team and the palliative care teams different may also

provide better insights into which patients need early

palliative care integration to optimize patient-centered

care.

REFERENCE

# Corresponding Author: Biren Saraiya, MD

Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine,

Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, Rutgers Robert Wood

Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, NJ 08901