Submitted - Februray 14, 2023 | Revised March 9, 2023 | Revised Manuscript Accepted - March 15, 2023 | ePublished - March 30, 2023

https://doi.org/10.52733/KCJ21n1-a1

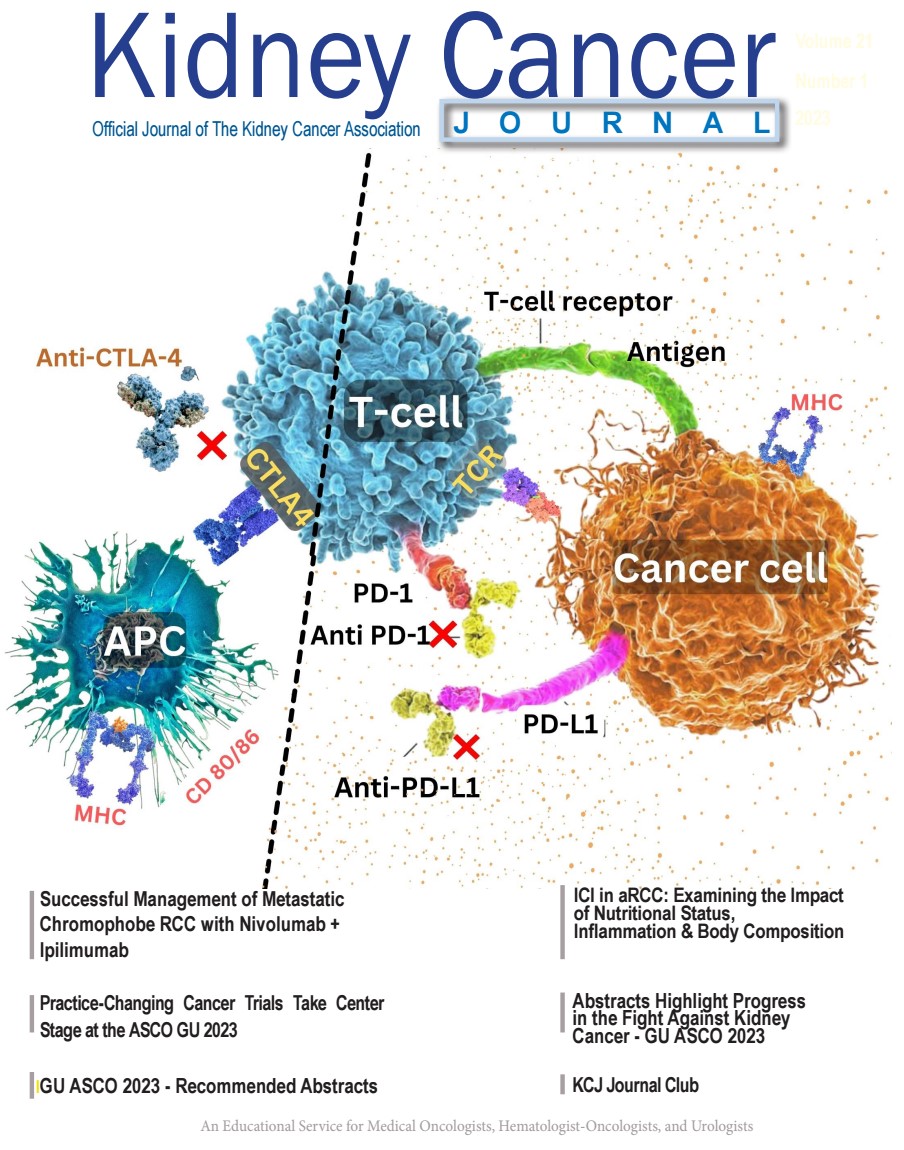

ABSTRACT

Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma (chRCC) is a rare histologic variant that is morphologically and molecularly distinct compared to the more common clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Due to the relatively lower incidence and lack of phase III trials, treatment for metastatic chRCC is often extrapolated from ccRCC. In this case report, we discuss a 58-year-old male with metastatic chRCC who was treated with nivolumab and ipilimumab and achieved a complete response. Though there are no definite predictive biomarkers, tumors that respond to checkpoint inhibitors (CPI) have a high immunogenic gene signature, high PD-L1 expression, MSI instability, or a high tumor mutational burden. Despite a comprehensive genetic profile predicting poor response to CPI, the current patient showed sustained radiologic response over three years. This case challenges the current paradigm of predicted response to CPIs in the setting of chRCC and shows that further biomarker driven research is needed to evaluate the efficacy of these agents in chRCC.

INTRODUCTION

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the

eighth most common malignancy

in the United States.1

RCC can be

divided into the more common clear

cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) and

non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma

(nccRCC). Chromophobe renal cell

carcinoma (chRCC) is the third most

common histologic variant of RCC,

accounting for 5% of cases.2 Although

computerized tomography (CT) is

the preferred imaging modality in

diagnosis and staging, histologic and

molecular analysis are required to

differentiate the histologic variants

of RCC. chRCC can be differentiated

by its characteristic aneuploidy with

the entire loss of chromosomes

1,2,6,10,13, and 17. The high

expression of mitochondrial gene

mutations and accumulation of

abnormal mitochondria suggest that

the organelle is important in the

pathogenesis of chRCC.3 ChRCC can

also occur in autosomal dominant

genetic syndromes such as BirtHogg-Dube’ and tuberous sclerosis

complex.3

There is limited evidence

regarding the first-line treatment

of metastatic chRCC.2 VEGFRTKIs (cabozantinib and sunitinib)

and mTOR inhibitors (everolimus)

have traditionally been utilized in

the treatment of nccRCCs due to

their proven efficacy in ccRCC.4

Nivolumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, has

also shown promise in treating

ccRCC resistant to VEGFR-TKIs,

but there are limited evidence in the

current literature addressing their

efficacy in the treatment of chRCC.2,5

We present the case of a patient

with cabozantinib-resistant chRCC

successfully treated with nivolumab

and ipilimumab.

CASE PRESENTATION

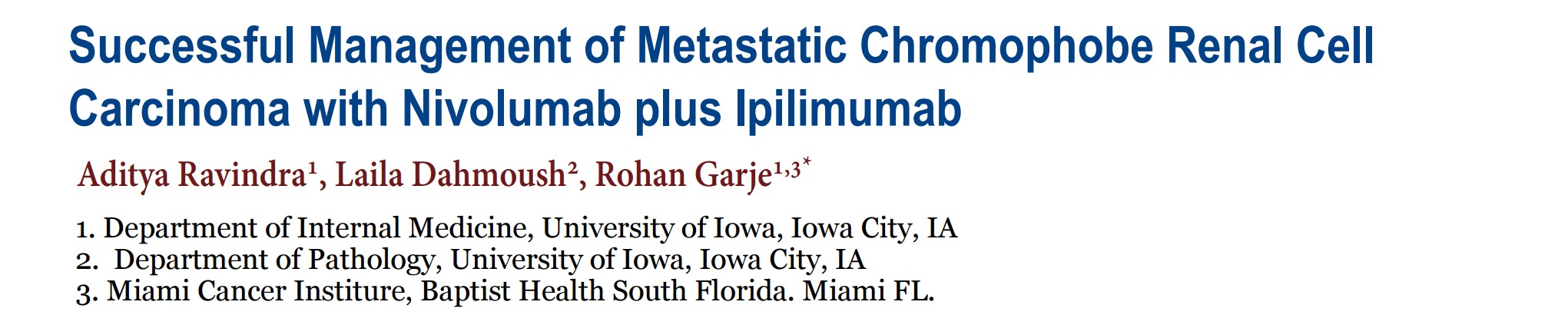

The patient is a 58-year-old

Caucasian male who initially

presented with left flank and lower

abdominal wall pain associated with

a 30-pound weight loss over one

year. Magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) of abdomen showed a large

left renal mass with invasion of the

left renal vein. PET/CT confirmed

FDG avid left kidney mass. (Figure

1) Biopsy of the mass confirmed

chRCC. Subsequently, he underwent

left nephrectomy with lymph node

dissection and adrenalectomy.

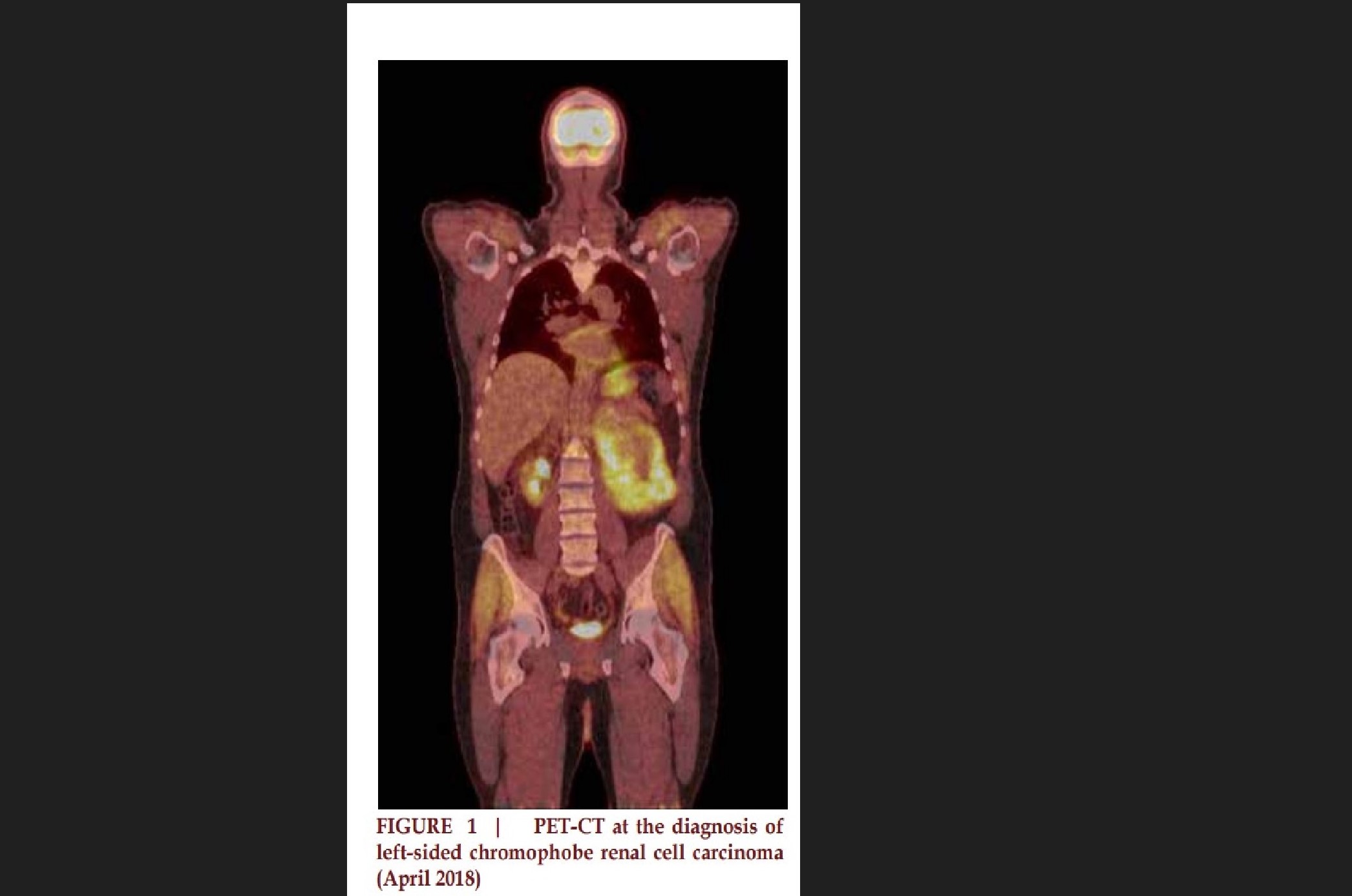

Pathology confirmed chRCC

with extensive tumor necrosis,

lymphovascular invasion, renal

sinus and perinephric fat invasion.

(Figure 2A & 2B) The surgical

margins were negative as well as

the lymph nodes and adrenal gland

were negative for metastatic disease.

Reassessment after surgery with CT

and bone scan revealed a solitary lytic

lesion in the first lumbar vertebrae,

and the patient received 30Gy/3fxs

stereotactic body radiation to the

area.

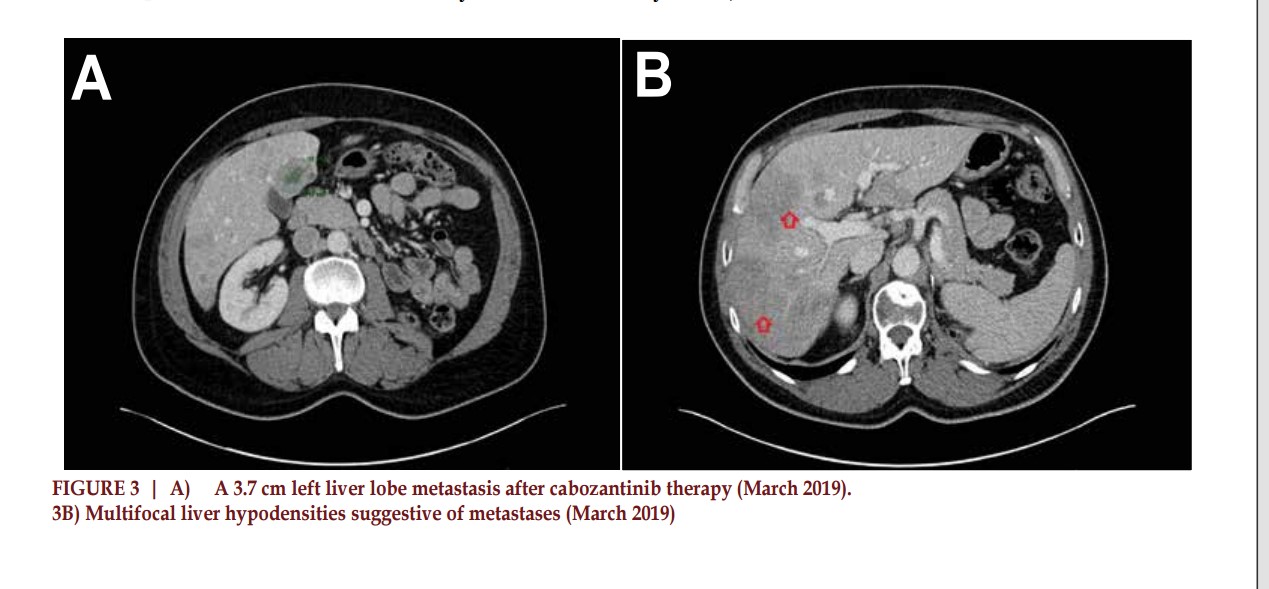

Subsequent restaging with

CT showed disease progression with

biopsy-proven liver metastases two

months after surgery, and he started

first-line systemic therapy with

cabozantinib 40 mg daily. Due to

the development of severe hand-foot

syndrome, the dose of cabozantinib

was reduced to 20 mg daily. Despite

six months of therapy, the patient

continued to have significant disease

progression, including new sites of

metastases in the lungs. (Figure 3A

& 3B). At this point in the disease

course, therapy was switched to

dual checkpoint inhibitor therapy

with nivolumab and ipilimumab.

Following the fourth cycle of this

regimen, reassessment with CT

showed partial response with

improved liver metastases and

resolution of the lung metastases.

However, immunotherapy was

discontinued after 5 months due to

development of an immune-related

adverse event (IRAE) in the form

of polyneuropathy causing Bell’s

palsy, dysphagia, and bilateral lower

extremity weakness. Brain and spine

imaging was negative for metastatic

disease or stroke. Cerebrospinal

fluid analysis showed an increase

in protein levels but was otherwise

unremarkable for infection. He was

treated with a prolonged tapering

dose of high dose prednisone with

gradual improvement of symptoms.

Despite stopping therapy after

5 months due to IRAEs, he has

ongoing complete response in the

liver, lung without any evidence of

active cancer for over 3 years now

(Figure 4). Also, he has recovered

from the IRAEs.

DISCUSSION

Although localized chRCC can be managed with surgery alone with excellent outcomes, metastatic disease requires the addition of systemic therapy with palliative intent and is generally associated with poor outcomes. The ASPEN phase II randomized control trial of 108 nccRCC patients showed everolimus, when comparable to sunitinib, showed improved overall response rate (33% versus 10% respectively).4 Within VEGFRTKIs, cabozantinib has been shown to have improved progression-free survival when compared to sunitinib in randomized controlled trials.6 After finding resistance to cabozantinib, we initiated second line therapy with nivolumab plus ipilimumab. In a retrospective analysis of 39 patients with nccRCC treated with nivolumab with or without ipilimumab, only seven patients showed objective response 6 months after therapy initiation.7 This is in comparison to the phase 3 CheckMate 214 trial that showed objective response rate of 42% in patients with ccRCC treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab treatment in first line setting. In another review by Bersanelli et al, the objective response rates with CPIs as monotherapy or in combination with other TKIs in chRCC ranged anywhere between 0% to 28.5%.8 The studies evaluating nivolumab plus cabozantinib, atezolizumab plus cabozantinib and pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib showed objective response rates of 0%, 11% and 13.3% respectively.8 Overall the decreased responses in chRCC when compared to ccRCC can be explained by the unique molecular pathogenesis with lower PD-L1 expression, microsatellite stability, and low tumor mutational burden (TMB) in chRCC.2 Targeted genomic sequencing with FoundationOne testing which combines DNA and RNA sequencing to identify common genomic alterations and complex nucleic acid fusion events was performed on the patient’s tumor specimen. The tumor was also found to be MSI-stable with a TMB of 4 mutations per megabase. PDL1 immunohistochemical analysis revealed a tumor proportion score of 1%.

Despite the lack of any predictive markers of response to checkpoint inhibitors on the genomic profile, our patient responded well to combination immunotherapy, albeit with serious immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). A couple of retrospective studies in patients with metastatic RCC treated with CPI revealed a correlation between the incidence of IRAEs and improved oncologic outcomes.9,10 The exact mechanism underlying this association is unclear. One hypothesis is bystander effect of activated cytotoxic T-cells in an organ with low-level inflammation that is potentiated after an IRAE with CPI therapy. In particular, local inflammation caused by IRAEs may activate the immune system and lead to an increased antigen presentation, release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and recruitment of immune cells to the tumor microenvironment. This could lead to an increased efficacy of the CPI therapy, as the immune system recognizes and responds to the tumor antigens. In a post-mortem study of patients with fulminant myocarditis secondary to CPI, T-cell receptor gene sequencing revealed similar high frequency TCRs in T cells om myocardium and tumor tissue.11 Another study revealed similar T-cell clones and antigens in the tissue obtained from the site of IRAEs and tumor.12 Though the onset of IRAE is a potential clinical marker of response to CPI, it is critical to identify those individuals at risk before therapy and understand the underlying mechanism that can aid in enhancing oncologic outcomes while minimizing serious IRAEs.

SUMMARY

In summary, while CPIs have shown some promise in the treatment of metastatic chRCC, more biomarker driven research is needed to fully understand their effectiveness in this specific subtype of RCC. Despite having low PD-L1 expression, MSI-stability, and a low TMB, our patient had a durable response with nivolumab and ipilimumab. Additional studies of nivolumab and ipilimumab are needed in a larger cohort of metastatic chRCC, along with further elucidation of mechanisms of IRAEs.

ABBREVIATION

REFERENCE

* Corresponding Author: Rohan Garje, MD Chief of Genitourinary Medical Oncology, Miami Cancer Institute, Baptist Health South Florida 8900 N. Kendall Drive | Miami, FL 33176 Email Id: rohan.garje@baptisthealth.net